The entries, in the 3/39th Journal are cryptic and sterile in their descriptions. Entry at 0745 on the 8th November: 1st lift A Co off Fort at 0714 into LZ White 1 (852694) at 0720: 2d Lift A Co off Fort at 0726 into LZ White 2 (856697) at 0731: 3d lift A Co off Fort at 0735 into LZ White 3 (857688) at 0744.

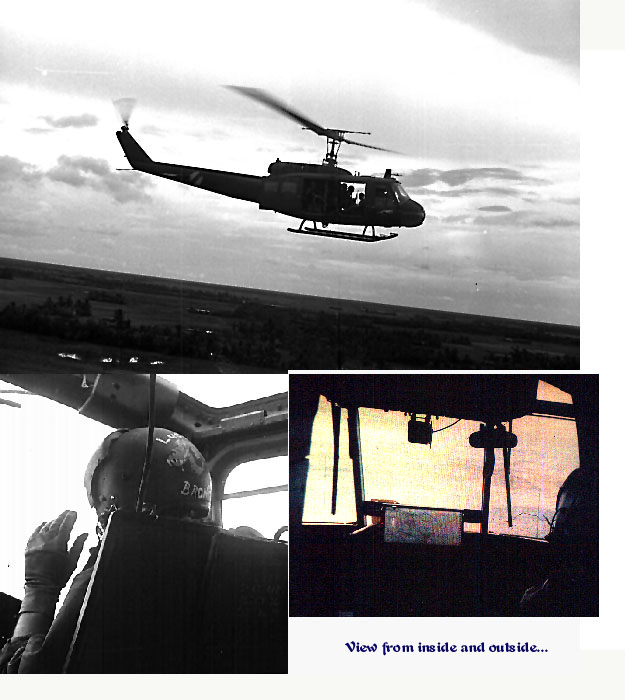

It was nice to be up in the air. For those few minutes it appeared that you got away from the danger on the ground which was ever-present. You certainly got away from the stifling heat, especially on this morning where the air was humid and still. The helicopter blades aided the ventilation, with breezes blowing through the wide open doors. As the helicopter gained altitude it ran across cooler currents of air, increasing safety and comfort. From there you could survey the wide expanse of the Delta, the breadbasket of Southeast Asia. The many rivers meandered left and right, creating odd formations and shapes and, sometimes almost meeting again to form a near circle. You could see the huge potential it had to feed not only the local population, but a large chunk of the world with nutritious rice. You could also see what the war had done by 1967-Bomb craters in every direction with large expanses of former productive rice field lying fallow, no longer being worked as the farmers were forced either into local concentrated hamlets or forced into the crowded urban centers, to survive by their wits.

The peasants of the Delta had no peace in many decades. I had never seen the kind of poverty which was apparent as we searched their palm leaf covered huts. The hard tables which served as beds, a few woven mats, a mosquito net, a pot, clay barrels to catch the rainwater, a few worthless French colonial coins, a chicken or two, a few ducks and maybe a pig is all the possessions they had and the real rarity was to see them all in one farm compound. A radio, razor blades, a spool of wire, a picture of someone in guerrilla uniform would be enough to earn them a helicopter ride to face interrogation by their army intelligence and an uncertain fate. The older ones were the only ones left, while encountering a youth of fighting age would immediately draw suspicion. The old ones would often meet us in their huts, bowing and humbling themselves and offering the only libation available to them, a small glass of hot water. Several times I heard them ask, “linh Phap?”, and I knew enough Vietnamese by then to know they mistook us for French soldiers. I would say: “Khong phai linh Phap. Linh My,” not French soldiers, American soldiers. Of course it didn’t make any difference to them, Chinese, Japanese, French or American, we were all there to fight their people and brought them the death and destruction of war.